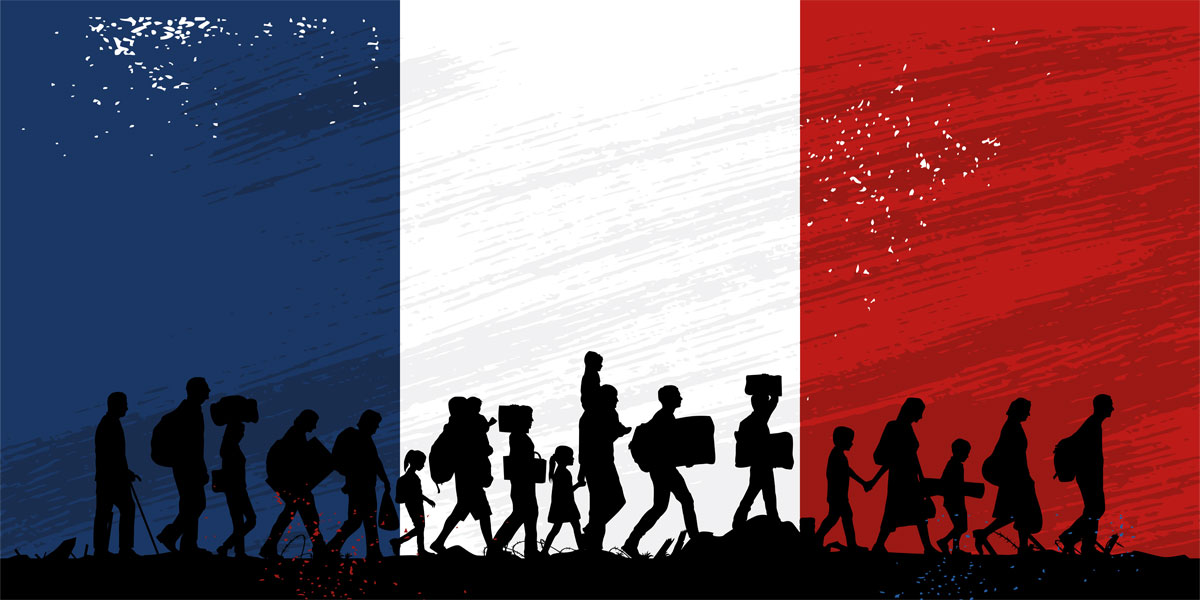

France’s projected image of liberty, equality and fraternity is being challenged by activist groups who say undocumented migrants face imperial injustices.

There are almost 400,000 undocumented migrants currently residing in France. Since 2017, deportations increased by 20 per cent in 2018, compared to 14 per cent the year before. Migrant aid groups say France has detained more migrants than any other country in the EU, most of whom come from North African nations.

In 2018, France also passed a controversial immigration and asylum bill. Its measures double the amount of time people can be detained.

“For us, it’s clear that this immigration — a forced immigration — is linked directly to the colonial destruction that so many countries have gone through,” said Jean- Claude Amara, the co-founder of Droits Devant, a group that surfaced in 1994 to defend migrant rights.

Amara said he works with the leaders of different activist groups to “unite the struggles of common factions.” These include La Chapelle Debout, an anti-racist activist group advocating for migrant documentation and housing, and the gilets noirs, who support allocating French citizenship to undocumented African migrants. Obtaining citizenship, Amara believes, opens doors to stable employment, housing and social security, allowing migrants the dignity of life beyond just survival.

A 2017 government report found that many illegal migrants do labour jobs like construction, catering or cleaning. This accounts for a fundamental part of the French economy, propping up industries from tourism to trade.

Read also: Netflix’s ‘Living Undocumented’ is a Difficult Series to Watch, and Exactly Why We Should

Earlier this year, protests staged by the gilets noirs against catering company Elior and the Hotel Ibis chain brought to light the extent to which many migrants are exploited, underpaid and taken advantage of by their employers. Elior, in particular, is contracted by the French state’s detention centres, meaning that many migrants are forced to provide cleaning and catering services to the very institutions that ultimately decide their fates.

Without citizenship, migrants cannot legally work or reside in France. In 2007, a decree to curb illegal immigration declared that the only way for migrants to obtain citizenship was if their employer submitted their documents to the prefecture. However, instead of doing so, many employers — wary of being penalised for employing undocumented workers — chose to fire employees they suspected resided in France illegally. Others continue to use the liminality of migrants’ positions to exploit them, knowing that if their workers complain, employers can go straight to the police.

Amara recognises that the problems linked to migration are systemic. Many migrants who come to France are forced to flee their home countries which have been ravaged by colonialism.

“We are, first and foremost, anti-colonial fighters”, says Amara. “For us, it is clear all the sans-papiers (those without legal papers) who come from the Global South to the Global North, are risking their lives, leaving their parents, their children and their culture behind.”

Read also: A Timeline of Global Migration

Last year, many anti-colonialism groups and their members occupied major Parisian landmarks like the Charles de Gaulle airport, the state’s launchpad for deportations, and the Panthéon, a tomb housing cultural French icons like Victor Hugo, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire. The occupation laid bare the irony of a colonial state celebrating its foremost thinkers who championed universal human rights yet failed to extend the same rights to migrant workers.

For current President Emmanuel Macron, immigration remains a tough problem that requires a tough solution. He argued in September 2019 that previous left-wing governments had “ignored the migration problem for decades”, and that he wanted to “tackle the issue head-on”.

But according to Amara, those in power do not have a problem with this because the bourgeoisie does not encounter it.

That is why asserting their humanity is at the very heart of the gilets noirs’ battle. While fighting to be seen as more than just a “problem” to be solved, the group has proved they are not afraid to reclaim the rights that France has denied them. Moreover, they have also succeeded in making themselves visible. For Amara, this is one of the movement’s most significant victories.

“When the sans-papiers began their fight, France was shocked to discover that each migrant had a smile, had emotions, had intelligence, and had something to say. This community that they were used to thinking of as hidden in the shadows had now dared to come into the light,” he said.

This story first appeared in the 2021 print issue of Truly Belong under the title “Coming to Light”.

- Undocumented Migrants in France are Fighting Imperial Ideology - 8th April 2021